“It's easier to hold your principles 100 percent of the time than it is to hold them 98 percent of the time.” - Clayton Christensen

Finance and People Operations leaders come face to face with ethical challenges more frequently than leaders in other functions. They are often tasked with being the ethical compass of an organization.

Ethical issues present themselves more frequently when business challenges arise. Finance and People Operations leaders are often the first to see the big problems in the business and are usually enlisted to fix things. These problems range from people issues (conduct, termination, etc.) to lawsuits to liquidity problems (cutting headcount, renegotiating contracts, handling covenant defaults etc.)

I moderated a virtual group discussion recently with peers in finance and people operations roles. The topic for conversation was “ethical challenges in the workplace.” Even I was surprised with the level of interest in the topic — and know it will be one our group revisits in the future.

The interest level is driven by three things:

(i) ethical challenges are more common than we would like to admit publicly;

(ii) there is a lot of grey area in decision-making (i.e. most don’t deal with patently illegal actions); and,

(iii) there is a lot of subliminal pressure to prioritize the interests of the company and its shareholders above those of employees, customers or other stakeholders.

In this piece I will touch on a few examples of common ethical challenges faced by Finance and People Operations leaders.

A. Commission vs. Omission

The root of the ethical conflict: How much and what to disclose to whom

(i) What to disclose to investors — existing or potential new investors?

(ii) What to disclose to potential new hires or existing employees who ask about company performance?

The common answer

Vis-a-vis investors:

With existing investors — Put your best foot forward. All companies have positive and negative things happening. Your business is no different. Just stress the positive. When answering questions, especially with regard to a metric that is sub-par, do your homework and “massage” the data to present that metric in the best possible light.

In investor diligence — Only answer exactly what is asked. Don’t volunteer additional information (unless it makes the company look good). New investors (especially VC or PE firms) are “big boys”; there is no reason to help them do their diligence.

Vis-a-vis employees:

Company information is disseminated on a “need to know” basis; a lot of stuff is above certain employees’ pay grade.

Don’t tell people about business challenges or shrinking cash balances (even VP or higher) as it might scare them and cause employee churn or create unnecessary drama (take focus away from productive work).

My preferred approach

I aim to adopt the worldview of the “Reasonable Optimist” (as explained by Morgan Housel in his recent essay). He reminds us that in the short term things will break, targets will be missed and businesses will underperform expectations; and, that over the longer term we will make great progress.

For me as a leader in the workplace, that means:

(i) Be transparent;

(ii) Put the challenges in context (especially for employees with less start-up experience);

(iii) Convey confidence (rooted in realism) that the Leadership Team is working collaboratively to solve the problems; and,

(iv) Empower employees to suggest ideas to solve the priority challenges.

B. “Everyone Else is Doing It” — Conformity vs. Morality

“Move fast and break things. Unless you are breaking stuff, you are not moving fast enough” - Mark Zuckerberg in a 2009 interview with Business Insider.

This now famous quote, originally targeted at product development, has morphed into a general piece of advice on operating in fast growing companies. “Breaking things” has expanded to apply to all “rules” that seem arbitrary. Organizations prefer that everyone follow their “rules,” but are unlikely to penalize someone for breaking many of these informal “rules.” The justification for breaking rules is typically that the actions taken in contravening the rules will contribute positively to a faster growth.

The root of the conflict: Do the rules apply equally to everyone?

Let me offer an example here.

Most businesses have a “rule” about promotions and pay increases. Promotions occur at specific times, once or at most twice per year. Pay increases are allocated in the budgeting process—typically ~5% of the total salary (split by department) is set aside for annual raises. These two “rules” are clearly communicated to all functional leaders, and documented in shared spreadsheets where the total funds set aside for salary increases for each team is spelled out.

Individual functional leaders are then asked to propose raises and promotions for their team members within these constraints. Once all the input has been collected there is a meeting involving the CEO, People Operations leader and Finance leader to review the inputs submitted by each functional leader.

The common outcome

The Finance and People Operations leaders usually set an example by keeping their recommendations around promotion timings and total merit increase amounts within the “rules.”

Almost no other functional leader follows that example. Each of them propose merit increases substantially in excess of their pool. They always offer good reasons for their proposals. This behavior is self-perpetuating and reinforcing—each functional leader felt ok “breaking the rules” because their peers were doing it too.

It becomes hard for the CEO and/or Finance Leader to hold the line without appearing arbitrary. Requests from functional leaders may be cut back a little but never fully. And, thus the “rule” is no longer followed. But no one admits this and the fiction of this rule persists in budgeting and as a company norm. Until the next semi-annual meeting on the same topic when the same rule breaking occurs again.

Why this behavior matters

My experience is that the fastest way to create resentment and fuel mercenary behavior among employees is to allow inequities in pay and promotions to spread. Many CEOs naively believe that pay levels remain private. The reality is that people talk, particularly about both strongly positive and negative outcomes. Furthermore, most employees in finance and people operations have access to the pay of everyone in the organization.

My preferred approach

Organizations may have “low value” rules. Those should be eliminated or restructured. I use the decision-making framework popularized by Jeff Bezos on “One-way and Two-way Doors”, in thinking about rules that are important to follow and apply to everyone. For example using a corporate credit card instead of a personal credit card or even not following the expense policy is a two-way door (i.e. reversible easily and thus easier to overlook.) Compensation decisions, especially when such decisions have probably been communicated to the person in question are more akin to “one-way doors”, where reversing such decisions would cause more severe damage.

C. Multiple Truths or A Range of Potential Outcomes

“...the future should be viewed not as a fixed outcome that’s destined to happen and capable of being predicted, but as a range of possibilities and, hopefully on the basis of insight into their respective likelihood, as a probability distribution.”

Howard Marks, Risk Revisited memo September 2014 (my bold)

The root of the conflict: how to reconcile multiple different business forecasts

In a short time span (even just a calendar quarter), Finance leaders will generate multiple forecasts for the business. Different forecasts will be distributed to distinct audiences. These forecasts will range from most conservative (for the 409a valuation) to middle of the road (Board plan) to more aggressive (internal stretch plan) to most aggressive (fundraising or M&A plan).

I have been asked by Boards and CEOs to produce, present and defend projections that if achieved would produce very attractive returns to a new investor. I call this ask: “Make the model say…..” I have done it, knowing full well the probability of those projections coming true is very, very low. And felt uncomfortable about it.

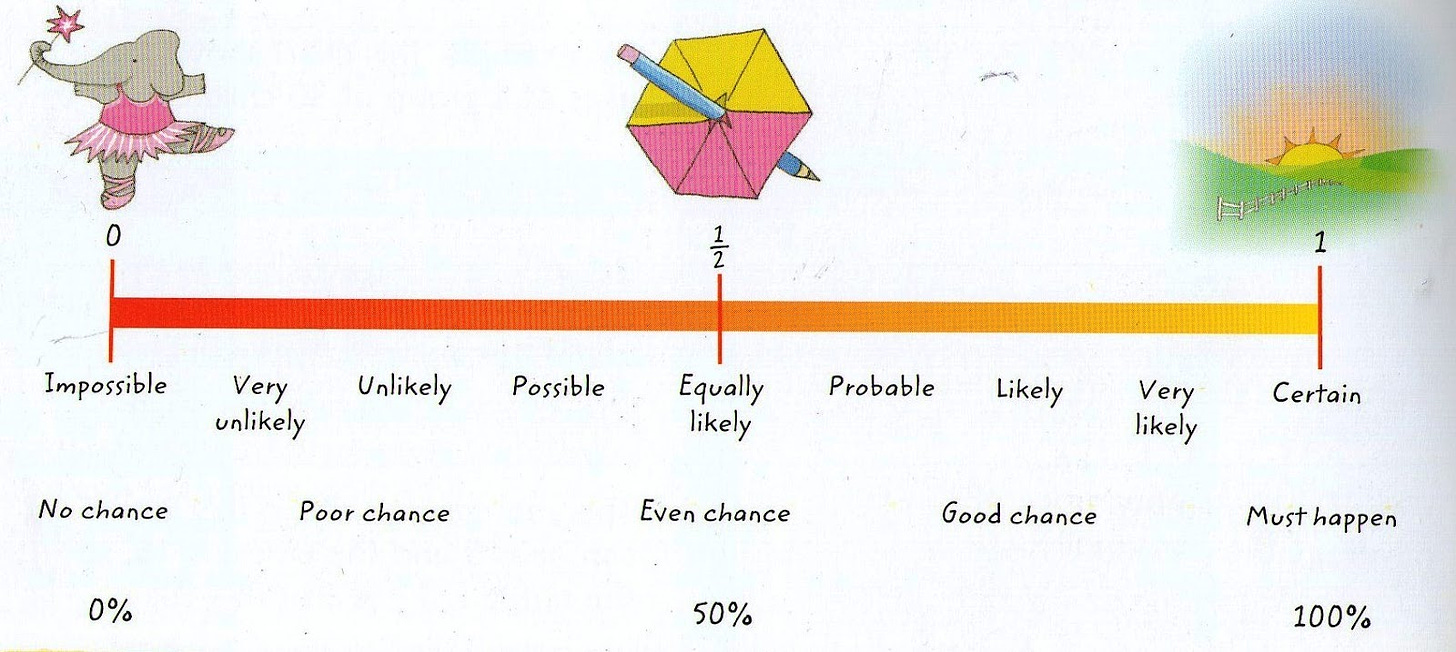

The ethical challenge arises because each individual financial model or business plan is presented as the most likely outcome to that particular audience. No one talks about each of these outcomes having a probability attached to it or assigns a probability (recognizing it is hard to quantify) as low, medium or high.

The reality

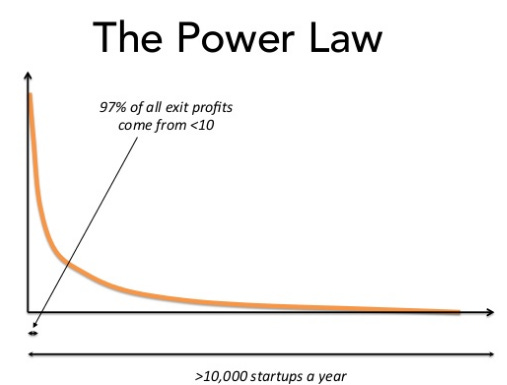

The positive return on investment earned by venture capitalists who invest their fund in a portfolio of high growth businesses are driven by just a few companies (graph below from Floodgate Capital).

And as Benedict Evans presented in 2018, the average venture-backed company does not generate a positive return for investors.

The common answer

The standard response to a concern about multiple models existing is that this is a game that everyone plays in private companies looking to raise money and hire top talent. Alex Danco writes about the unwritten rule whereby tech founders (and presumably their agents such as Finance leaders or recruiters) can stretch reality if there is a genuine effort “to bootstrap the future into existence.”

Another justification is to fall back on the logic of math and probability. After all, forecasts or models are the output generated from a range of inputs or assumptions that build up revenue and expenses. Using Howard Mark’s logic about future predictions (which I do subscribe to), each model variant can be viewed as one (or multiple) possible future outcomes. And all can co-exist as possible models of the future.

My preferred approach

One of the most important assets of all leaders, particularly Finance leaders, is their reputation, trustworthiness and credibility. There is often a question in employee surveys on “confidence in leadership.” The knowledge of the existence of multiple plans can contribute to eroding employee confidence in leaders.

I prefer having a single plan, approved by the Board which sets the targets for the company to operate against for the next fiscal year. Ideally the Board approves a detailed plan for the coming year and a high level 5-year plan. This high level plan is the one to be used with prospective new investors. If the company is overperforming in the near term, it would be reasonable to enhance out-year assumptions to reflect the better short-term performance.

Sadly, everyone recognizes that the 409a valuation is a “game” played by the company, the valuation firm, and the Board in an effort to set a believable yet low option exercise price. The earlier the company is in its history, the more the rules of the game are open to interpretation. It would be nice to be able to say that I have not succumbed to this pressure to present an attractive 409a valuation (without a down round) to the CEO and the Board. Unfortunately I cannot say that.

D. Balancing the desires of employees and investors

The background

Beginning in the post-WWII era and lasting in some form into the early 1980s, there was an implicit social contract between US businesses and their employees. This social contract included long-term employment and some form of a pension. The contract began to dissolve in the early 1980s, and dissolved quickly.

I became cognizant of the business world in the early 1980s, a time when business ethics were heavily influenced by the writing of Milton Friedman.

Friedman ends a now famous article written in 1970 with the following: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Soon thereafter (and to this days) words such as “unions” and “collective bargaining” acquired a strong negative association.

The root of the conflict: How best to divide up the pie

On a regular basis, Finance and People Operations leaders are asked to opine on how generous the company should be with salaries, benefits, accruing vacation/sick days and severance. When there is information asymmetry, should the company pay market value for a new hire or take them on at a lower rate, if they don’t ask for more. The unstated underlying belief is that dividing up the pie (i.e. money) is a “zero-sum game”—if we offer more to some employees, other employees must get less, or investors must get less.

The common answer.

In a free-market system, where the company is not violating any regulations, it is fair to have pay disparities and pay people below market value for their work, if they don’t object. There is no legal obligation (in the United States) to offer meaningful severance, unless in return for a release signed by the terminated employee. Having employees on probationary periods makes sense to protect the employer against underperformance or poor fit, which further reduces employee rights to severance and potentially to benefits as well. It is perfectly reasonable to have 1-year vesting cliffs for option grants. I have had directors tell me that this allows them to bring on a senior leader with limited risk as that person can be fired before their one-year anniversary without any equity dilution to investors.

My preferred approach

I wrote about this topic in one of my first posts called The CFO Balancing Act. I acknowledge that I am an idealist. My approach is influenced by two principles: (1) The Golden Rule—treat others as you would wish to be treated; and, (2) John Rawls “Veil of Ignorance” which addresses how to design just social systems.

When the rubber meets the road, I have offered the following recommendations to CEOs:

(i) Pay market value and if cash is scarce hire fewer people so that everyone can be paid their true worth.

(ii) Be generous with benefits (especially healthcare related) and cover families (not just the individual employee); and, incentivize employees to avoid doubling-up on insurance by offering a substantial monthly payment to those who decline coverage by proving they have coverage through their partner or parent.

(iii) Be kind with severance payments including covering COBRA for an extended period of time. Finding a new job after being terminated is hard. An incredible role model for how to deal with terminating employees was the public letter Brian Chesky wrote in early May 2020.

(iv) I would also love to reform a few things about the option system including vesting and time to exercise post termination. That has been beyond my ability to change.

I defend my approach to CEOs and investors by arguing that the long-term benefits of treating employees well far outweighs the short-term costs. Companies who do this consistently will attract better talent, retain talent for longer, and employees will be more productive while at the company.

Finance and People Operations leaders are often the ethical conscience of a business. That can be a lonely place. I encourage us to talk about the challenges we face—with our teams and with colleagues in similar roles in other organizations. My hope is that by talking about the ethical challenges in the workplace we feel less alone. And then will gain confidence to listen to our gut and call out things for further discussion that seem inappropriate.